This blog is the first of a two-part series exploring the project. In this first blog, we focus on why and how we engaged young people in this way. Part two, coming up next week, will look at the outcomes of the session and how the young people would improve Edinburgh if they were in charge.

Cities: Skylines – what is it, and why did we use it?

Cities: Skylines is a hugely popular single-player open-ended city-building simulation game, first released in 2015. Since then, lots of expansion and content packs have been released, and the game can now be played on PC, Mac, PlayStation, Xbox and Nintendo Switch. Cities: Skylines has its origins in transport simulation, but it has developed over time as a comprehensive city building game. Players are tasked with managing public services, transport and urban planning, all while balancing the needs of citizens. Inspired by classic titles like SimCity, Cities: Skylines has become a fun and engaging way to learn what it takes to be a city planner, with thousands of user generated modifications adding richness and realism to the player experience.

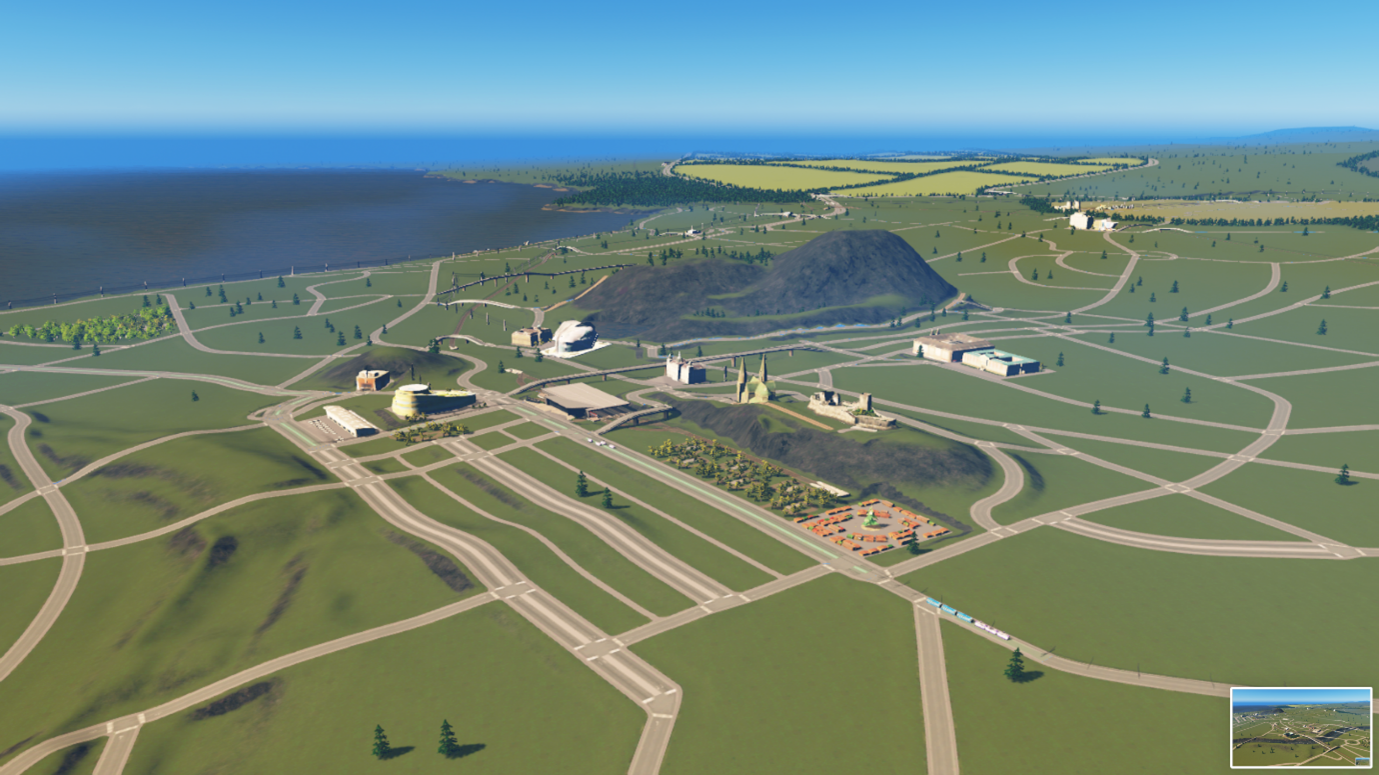

Players usually begin with a blank map and take the position of mayor building a whole new city from scratch. In this context, however, we were keen to situate our engagement in the realities of their home city. This led us to build a base map modelled on the streets and neighbourhoods of Edinburgh (building upon work by hibee85). This included the main road, rail and tram network, rough locations of city neighbourhoods, and landmarks like Arthur’s Seat, Edinburgh Castle and Murrayfield Stadium. Our focus was on creating a scaled-down, sandbox version of the city that players would recognise, all within the constraints of the game. So the game would run smoothly on laptop computers, we only included a handful of buildings, so some imagination may still be needed! You can see some images of the base map from two vantage points below.

Often, it can be difficult for young people to imagine how decisions are made in places and spaces, as they lack the lived experience of seeing it work first hand. We chose to pilot the use of Cities: Skylines for its potential to bring city design and decision-making to life. This has already been done in other countries to great effect, but we believe we are the first in Scotland to try this out. In Cities: Skylines, players are in control of their own experience and have significant choice to design on the terms that suit them. At the same time, and as with real life, all decisions in the game have short, medium, and long-term consequences. These can be monitored through in-game metrics and notifications, such as:

- City population

- Happiness of citizens

- Land value

- Levels of demand for housing, commercial, and industrial land uses; and

- Current demand and supply for electricity and water.

Importantly, the game is also user-friendly and intuitive, making it easy for new players to pick up and get playing quickly.

The Session

We spent one full day working with 15 and 16 year olds in an S5 Geography class . A couple of the pupils had previously played Cities: Skylines, but everyone else was new to the game. We began the session by looking at a big map of the catchment area for Tynecastle High School, and talked about what was already good in the area and what could be better and improved. This enabled us to ground the project in their real lived experience.

The map below shows the thoughts and ideas of the group and we used this to begin crystalising thoughts and feelings of what makes for a good/functional city and what does not. We used this in their first introduction to the game, whereby they played with a generic city map where some of them determined to look at improving the city, and others looked at ways they could destroy it. For instance, some introduced different types of housing, industry, and transport. Others experimented with removing powerlines or setting up polluting industries in the middle of neighbourhoods.

The young people’s experiments led us to discuss as group the principles of a 20-minute neighbourhood. The rest of the session focused on a ‘Design Jam’ where pupils worked on to create their version of a 20-minute neighbourhood on the gamified version of Edinburgh.

Learnings Along the Way

Participants were very engaged and immersed in the game and thrived on being able to try out different ideas to build better neighbourhoods. Some were able to build highly functional city centres or suburbs, while others learnt from trialling approaches that ultimately proved unsuccessful. This also surfaced opportunity to reflect on the different ways young people determined to play the game, and built upon everyone’s understanding of what makes for a good/successful city or neighbourhood.

Another Key insight was to see that some were most interested in approaches that may have similarities to the work of civil engineers, while others more comfortably took on the role of town planner, for example. By seeing the different ways pupils play the game and the outputs they were coming out with, it became clear that this is a powerful tool for describing and giving simulated experience for various career opportunities in the built environment – from builders, surveyors, architects, engineers, planners, and even politicians. Cities: Skylines can therefore be both a curricular approach to learning about developed cities, and useful for raising awareness of the many careers available in the sector. It can also serve as a useful way of gathering young people’s views about improving where they live!

What’s Next

Next week, in part two, we will reflect on the cities and neighbourhoods created by the young people we worked with. Through this, we get an insight into what pupils want for the future of their local area and Edinburgh as a whole. If you would like to know more about this project, you can get in touch using our contact form or by reaching out to our project lead Dr Jenny Wood directly, at jenny.wood@aplaceinchildhood.org.

If you’d like to give the base map we created a play, you can download it here.

Header image source: Game © Paradox Interactive AB www.paradoxplaza.com